Here in the spring issue of Parabola magazine, you’ll find essays by beloved Pulitzer Prize winner Mary Oliver, Zen Master Peter Coyote, and Wisdom teacher Cynthia Bourgeault, along with my piece about the Irish miracle worker, Valentine Greatrakes (1628-1683).

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious,” wrote Albert Einstein. “He to whom the emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand wrapped in awe, is as good as dead.” I hope the following excerpt from my essay will remind you that Earth is a magical home, powered by love, filled with surprises.

If you enjoy reading about Greatrakes, you will eventually be able to catch up with him in The Last of the Magicians, my third historical, in progress.

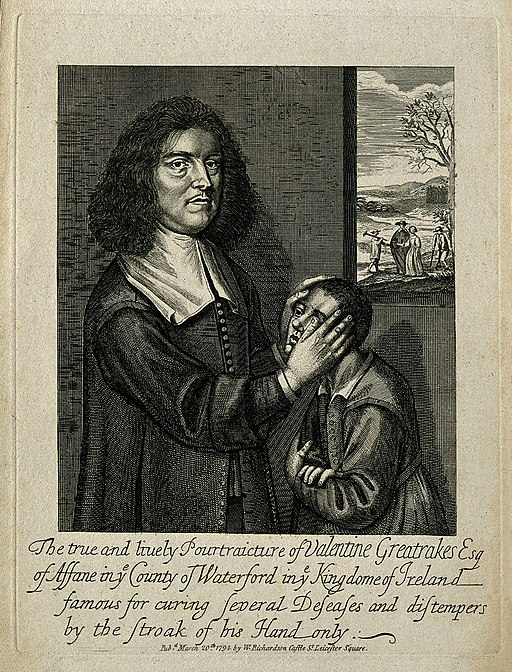

The Inscrutable Cures of Valentine Greatrakes

At the dawning of the Age of Reason, before Isaac Newton’s mathematical proofs poured light on a shadowy universe, Valentine Greatrakes (1628-1683) healed suffering bodies with his hands. The Irish Stroker, as he was known, cured young and old of tumors and wens, paralysis, arthritis, assorted pains, eczema, deafness, blindness, and possession by demons. Hailed by some as an apostle, condemned by others as a fraud, he was a sensation that roused the interest of natural philosophers, churchmen, physicians, and even the king.

Crossing stormy seas to arrive on the coast of Somersetshire in January of 1666, Greatrakes would challenge the cessationist doctrine that miracles had ceased after biblical times. No one argued that God lacked the power to intervene, but Jesus Christ and the Apostles had already proven the truth of the Gospel, rendering miracles superfluous. In early modern England, faith may have rested properly upon the Word alone, but the time period was imbued with supernatural phenomena and signs of God’s providence. Female prophets went without food for more than a year. Baptists and Quakers restored the sick and raised the dead. Charles II, by virtue of Divine Right, applied his thaumaturgic touch to cure victims of scrofula—a tuberculosis infection of the glands in the neck.

Among an eclectic cast of healers, religious enthusiasts, imposters, and frauds, Greatrakes distinguished himself by advancing no agenda other than to heal the sick. A member of the landed Anglo-Irish gentry, he was a wealthy man who accepted no payments for his services, unlike the common quacks. His charitable work drew particular scrutiny from members of the recently formed Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. In Greatrakes, the virtuosi saw the opportunity to employ Francis Bacon’s new empirical method of investigation and to establish, once and for all, if phenomena truly existed.

The Stroker was drawing crowds in the county of Warwickshire when the king and his court returned to Westminster from Oxford, where they had fled to escape the bubonic plague. The idea of contagion existed in the seventeenth century even if the method of transmission was not understood and the causative organism, Yersinia pestis, was not yet known. Robert Hooke had just begun to study fleas and plant cells under his gold-tooled microscope.

Lacking understanding of the plague’s etiology, physicians prescribed sweat-producing cordials, remedies of angelica and rue, costly Venice treacle, and blood-sucking leeches. Given the limitations of Galenic medicine based on the theory of the four humors, physicians might almost be forgiven for absconding from London with their wealthy clientele during the epidemic. At least the apothecaries stayed behind to offer up antidotes such as unicorn horn and powder of toad.

To continue reading more from this issue and purchase a copy of Parabola magazine, click here.